Sue McPherson’s middle school Farm to Fork studio is showing Northern Cass learners careers and opportunities in agriculture, as well as all the ways agriculture touches their lives. The studio is part of Northern Cass’s approach to personalized learning and a way to prepare them for their lives after school.

HUNTER, N.D. — When the middle school at Northern Cass School District incorporated a “studio” system, where kids can pursue interests and passions outside of the normal school subjects, Sue McPherson started thinking about something that’s all around the school.

Agriculture.

“We’re in the middle of a corn field, or soybean field this year,” the Level 6 educator said.

The 25-year educator — as Northern Cass prefers to call teachers — has a longstanding interest in agriculture. She grew up a farmer’s daughter. During college, McPherson didn’t get a traditional job doing something like waiting tables — she had to be available to go home and dig or disc or drive truck, “which I thoroughly enjoyed,” she said. Her husband is an aerial applicator, and her sons are involved in various avenues of agriculture, including farming, seed sales and livestock.

While Northern Cass School District encompasses rural areas and small towns, that doesn’t mean it’s populated by farm kids. McPherson said few of the learners — the term Northern Cass prefers for its students — are growing up on farms, and she saw an opportunity to open their eyes to where their food comes from and to the opportunities in agriculture they might not see.

The 25-year educator — as Northern Cass prefers to call teachers — has a longstanding interest in agriculture. She grew up a farmer’s daughter. During college, McPherson didn’t get a traditional job doing something like waiting tables — she had to be available to go home and dig or disc or drive truck, “which I thoroughly enjoyed,” she said. Her husband is an aerial applicator, and her sons are involved in various avenues of agriculture, including farming, seed sales and livestock.

While Northern Cass School District encompasses rural areas and small towns, that doesn’t mean it’s populated by farm kids. McPherson said few of the learners — the term Northern Cass prefers for its students — are growing up on farms, and she saw an opportunity to open their eyes to where their food comes from and to the opportunities in agriculture they might not see.

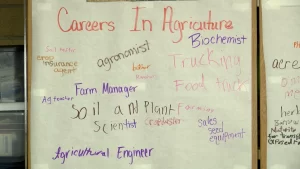

Learners might not realistically be able to see a future in farming, but they might not realize how many other vast careers are involved in the industry, McPherson said. Through the studio, the kids are choosing careers in agriculture to explore and are taking the reins on how they want to learn about them. Some have chosen things like soil science or plant science, while another is looking into sales at a large livestock and veterinary supply company.

Learners might not realistically be able to see a future in farming, but they might not realize how many other vast careers are involved in the industry, McPherson said. Through the studio, the kids are choosing careers in agriculture to explore and are taking the reins on how they want to learn about them. Some have chosen things like soil science or plant science, while another is looking into sales at a large livestock and veterinary supply company.

Beyond careers and life skills, the learners also are getting a hands-on lesson in where food comes from and how it gets to their plate.

“Everybody eats,” McPherson said. “There’s getting to be more and more people in the world and less and less farmland. So we really have to get behind the sciences and let these middle schoolers find the passion of their own if it’s in agriculture and let them run with it.”

Innovation at work

Northern Cass School District has a reputation for innovation and has moved in recent years to a focus on “personalized learning.” Personalized learning focuses on allowing “learners” — Northern Cass prefers that term because it has a more active connotation than “students” — to work at their own pace toward achieving proficiency at educational standards. Rather than being lumped only into classes by age, learners have both “social level” numbers assigned by graduation years and “learning levels” assigned by their proficiency in math and language skills.

Northern Cass School District has a reputation for innovation and has moved in recent years to a focus on “personalized learning.” Personalized learning focuses on allowing “learners” — Northern Cass prefers that term because it has a more active connotation than “students” — to work at their own pace toward achieving proficiency at educational standards. Rather than being lumped only into classes by age, learners have both “social level” numbers assigned by graduation years and “learning levels” assigned by their proficiency in math and language skills.

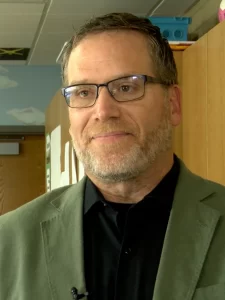

Superintendent Cory Steiner said their school is known as the “palace on the prairie.” It’s 25 miles northwest of Fargo and serves the communities of Argusville, Arthur, Erie, Grandin, Gardner and Hunter, though 34% of learners have open enrolled at Northern Cass from outside the district. That large open enrollment number, he feels, is a reflection of people wanting a big school experience in a small school environment.

Superintendent Cory Steiner said their school is known as the “palace on the prairie.” It’s 25 miles northwest of Fargo and serves the communities of Argusville, Arthur, Erie, Grandin, Gardner and Hunter, though 34% of learners have open enrolled at Northern Cass from outside the district. That large open enrollment number, he feels, is a reflection of people wanting a big school experience in a small school environment.

The studio concept, Steiner explained, was an attempt to “reset our middle school” and to give educators and learners more agency in education. The first attempt at doing so was a failure because it was too top-down, he said, while the current system was based in collaboration and conversation among administrators, educators, learners and parents.

The studios aren’t just electives but a way to dive into a subject and in doing so learn the things schools need to teach, like reading or math, along with life skills, and to do it all in a way that feels more natural and engaging. That will, the school believes, empower learners to be ready for whatever comes next, whether it’s college, career or military, and to see that the world holds more possibilities than they were aware.

“Their future is bigger than where they’re at currently,” he said.

While the Northern Cass High School has learners developing their own studios, the middle school educators are doing a lot of the idea generating. McPherson said that is, in part, because middle schoolers haven’t been exposed to a lot of the world and “don’t know what they don’t know.” Studio subjects have been vast, including fantasy football and cultures of the world.

McPherson described the process of learners choosing their studios as something akin to speed dating. Educators have a few minutes to sell their idea for their studio to each learner. Her first studio this year was on cursive writing, and she had a huge group join in. They ended up getting pen pals, and some learners have continued to correspond with theirs even after it was over, Steiner said.

McPherson described the process of learners choosing their studios as something akin to speed dating. Educators have a few minutes to sell their idea for their studio to each learner. Her first studio this year was on cursive writing, and she had a huge group join in. They ended up getting pen pals, and some learners have continued to correspond with theirs even after it was over, Steiner said.

While the cursive course was a success, McPherson feels she purposefully undersold her Field to Fork studio to keep her number of learners a bit lower. That has enabled it to be more personalized and allowed for many field trips — sometimes multiple in the same week.

The studio system is still in its first year, but Steiner said he’s received “exceptionally positive feedback.”

“When you empower learners, they can do some amazing things,” he said.

Setting up the future

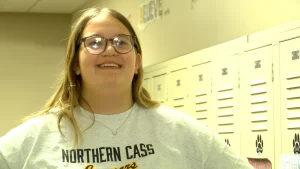

Mckenzy Albert, 13, is among the middle schoolers who chose McPherson’s Farm to Fork studio. The Level 8 learner said she just wanted to learn more about agriculture. Since her dad works with beef cattle, she has been focusing on dairy.

Mckenzy Albert, 13, is among the middle schoolers who chose McPherson’s Farm to Fork studio. The Level 8 learner said she just wanted to learn more about agriculture. Since her dad works with beef cattle, she has been focusing on dairy.

While she’s grown up in small North Dakota towns — Horace and now Page — she has not grown up on a farm. But agriculture has long been an interest of hers, and she’s getting a lot out of direction out of the class.

“I’ve learned a lot. I didn’t think it would be that fun,” she said. “It’s been more interesting than I thought.”

For her, part of the experience has been getting to “go face to face with the opportunities.” The learners aren’t learning just from books or websites. They’re tasting and touching agriculture, and they’re meeting experts and learning from them.

And they’re not just meeting the experts — they’re facilitating the meetings. For instance, Albert contacted the manager of the North Dakota State University dairy facility to set up a field trip for the class.

And they’re not just meeting the experts — they’re facilitating the meetings. For instance, Albert contacted the manager of the North Dakota State University dairy facility to set up a field trip for the class.

Those kinds of communication skills and opportunities aren’t just a coincidence of the studios — they’re part of the point, McPherson said. Through those experiences, the learners also pick up new vocabulary words and new skills that may come across more easily in a practical application than in a traditional classroom.

The studios also provide natural engagement, as the learners lead the way based on their interests.

“I’m excited to see what they come up with,” McPherson said.

Albert’s dad works for Leedstone, a Minnesota-based animal health and supply company. And now that she’s explored a bit, she can see herself working there someday, too.

“I think I’d be a good salesman,” she said.

She’s thankful for the people in agriculture who work hard to feed the world.

“It’s a blessing,” she said.

Steiner, who grew up on a farm, agrees.

Steiner, who grew up on a farm, agrees.

“It is what builds the foundation for this beautiful state and the amazing people,” he said. “I believe that ag is what gives us humbleness and humility. It has built integrity. And it’s what still makes North Dakota kind of a little known place and allows us to keep a very strong closeness and keep relationships always at the center of what we do.”

The new ideas for education that Northern Cass has developed may spread beyond eastern North Dakota. Steiner hopes they do. He and McPherson believe the lessons the learners are exposed to in the studios are more apt to stick with them than, as Steiner put it, the facts they learn for a test and then set aside.

McPherson hopes the learners see new career fields in agriculture, even if they don’t follow them. And even if their lives take them in different paths, they still will eat, and now they’ll know a bit more about the origins of that food.

“There are so many avenues they could take,” she said.